On June 29, 1998, after 91 years of struggle by Peguis First Nation, Canada confirmed it agreed with Peguis that the 1907 surrender of the St. Peter’s Reserve was void and legally invalid due to Canada’s failure to comply with requirements of the Indian Act of 1906. Canada and Peguis entered into negotiations to compensate Peguis for its loss of land and economic loss as a result of this illegal surrender.

On June 13, 2009, Peguis members voted in favour of the proposed settlement claim and the agreement was ratified by the parties on October 4, 2010. The total settlement amount was $126,094,903. Upon payment of settlement costs and legal fees Canada deposited $118,750,000 in to the Peguis First Nation Surrender Claim Trust. Of this amount $10,500,000 was set aside for a per-capita payment to the beneficiaries. The Surrender Claim Trust is separate from both the Implementation Unit and the Treaty Land Entitlement Trust.

1700’s

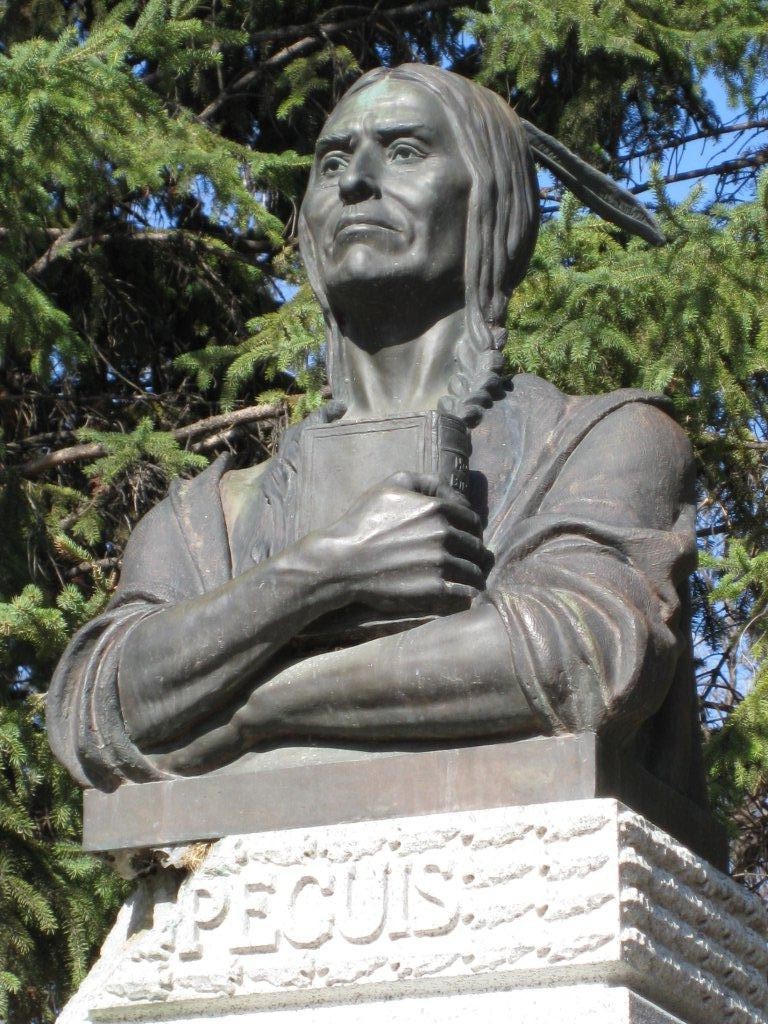

Chief Peguis and his Band settled in an area north of present-day Selkirk in the late 1700s

1817

Selkirk Treaty

Peguis and other chiefs signed the Selkirk Treaty in 1817. The treaty allocated land along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers to Lord Selkirk and his settlers for an annual rent of tobacco

1871

Treaty 1

1883

As early as 1883 a leading citizen of Selkirk, James Colcleugh, circulated a petition which called on the federal government to put the St. Peter’s reserve up for sale, as it was a “drawback to our growth and prosperity.” Colcleugh advised Lisgar M.P. A. W. Ross that if he could “devise some means of busting the reserve … your name will be immortalized!” Such sentiments were widespread in the West among townspeople and homesteaders near Indian reserves. It was felt that Indians held land far out of proportion to their needs, that they did not effectively use this land, and that their presence inhibited the growth and progress of a district. Prime agricultural land especially was thought to be wasted in the hands of Indian bands, even when these people farmed with success, as in the case of St. Peter’s and many other bands across the West. Beginning in the 1880s such arguments were used throughout Manitoba and the North West in letters, petitions and deputations to federal members of Parliament. After 1896 especially these campaigns were successful in securing the surrender of thousands of acres of prairie reserve land. As land prices in the Selkirk district steadily rose after 1896, people active in politics and commerce in the community, especially the Selkirk Board of Trade, began to promote the idea that the reserve should be opened up for sale.

1907

1907 Meeting & Vote

Reserve residents had been given only one day’s notice of the meeting called to consider surrender, and many did not hear and did not attend. The meeting was held at a time when people were out on Lake Winnipeg fishing and could not attend given only one day’s notice. One week’s notice at least should have been given for such an important meeting. The Commission found that the surrender agreement was neither partially nor fully read to all of those present, and what was read was in English only. The terms were not translated or explained in Cree or Saulteaux. The meeting was held in a small school house, and only one-half of those present could get in while others had to attempt to listen at the windows and door.

The vote was recorded in a controversial manner. Those present were asked to separate into two rows; those in favour to stand on one side, and those against on the other. There was a great deal of confusion for a time with people travelling from one side to another, and it was difficult to keep the two crowds separate. The commissioners found that it was “Just at that moment the Rev. Mr. Semmens called out at the top of his voice in the Cree language, ‘Which of you want $90 go over there’, indicating the affirmative side with his hand.” (Semmens was the Clandeboye Indian agent, a Methodist missionary, and a shareholder in the Selkirk Land and Investment Company.) The deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs Frank Pedley was present at the surrender meeting and had $5000 in a satchel which it was made clear would be distributed if the surrender carried, and if it was defeated “the satchel with its precious contents would go back to Ottawa.” The commissioners found clear evidence that up to the time of the “parading the satchel” before them, the band was not favourable to the surrender and had not asked for it. When the vote was taken it was found that 107 were standing in favour and 98 against, but no record of the vote was taken as was customary in elections for chief and councillors. There could well have been people there who had no right to vote as no attempt was made to authenticate band membership. Certain additions to the surrender document were made after the vote and were never voted on or ratified by the band, so that the surrender submitted to the vote was not the same as the one signed.

A variety of measures were used in an effort to sway votes in favour of surrender. Band member Fred Cameron described for the commissioners what took place before the vote was taken.

Just a few minutes before the vote was taken Mr. Semmons spoke to me ‘Fred, I want to see you for a minute’ and he took me to one side a little bit and asked me if I was on his side, the surrender side, and I said no, and he asked me what family I had, and I told him myself and wife and six children, that would be eight of a family altogether, and he pulled out his little pass book and started to figure and he said ‘You are getting some money today if you make the surrender, you are getting $4.50 per head and that would $3.40 you will get’, and he kept on figuring and said ‘You are getting 16 acres of land per head and you will get 120 acres’, and he kept on figuring and he said ‘Besides that you will get $90 a year from now if you surrender’. When he finished figuring he said ‘Now, you will be well-off getting all this, now will you surrender?’ and I said no, I would not.

1998

Void & Legally Invalid

On June 29, 1998, after 91 years of struggle by Peguis First Nation, Canada confirmed it agreed with Peguis that the 1907 surrender of the St. Peter’s Reserve was void and legally invalid due to Canada’s failure to comply with requirements of the Indian Act of 1906. Canada and Peguis entered into negotiations to compensate Peguis for its loss of land and economic loss as a result of this illegal surrender.

1998

Void & Legally Invalid

On June 29, 1998, after 91 years of struggle by Peguis First Nation, Canada confirmed it agreed with Peguis that the 1907 surrender of the St. Peter’s Reserve was void and legally invalid due to Canada’s failure to comply with requirements of the Indian Act of 1906. Canada and Peguis entered into negotiations to compensate Peguis for its loss of land and economic loss as a result of this illegal surrender.

2009

Surrender Settlement

On June 13, 2009, Peguis members voted in favour of the proposed settlement claim and the agreement was ratified by the parties on October 4, 2010.

The total settlement amount was $126,094,903. Upon payment of settlement costs and legal fees Canada deposited $118,750,000 in to the Peguis First Nation Surrender Claim Trust. Of this amount $10,500,000 was set aside for a per-capita payment to the beneficiaries. The duties and responsibilities of the Trustees are contained in the Trust Agreement.